VER Room

The Broken Ladder

The Broken Ladder

by Wantanee Siripattananuntakul

7/02 — 31/03/2018

House/Hope

After the Wang Tha Phra campus of Silpakorn University was indefinitely closed for construction (indefinite like the postponement of Thailand’s election date, the latter equally indefinite if not more so), the four faculties—Faculty of Painting, Sculpture and Graphic Arts, Faculty of Architecture, Faculty of Archaeology, and Faculty of Decorative Arts—have scattered to different sites. The Faculty of Archaeology to which I belong has moved its operations to the Sanskrit Studies Centre near Thawi Watthana canal since the middle of 2016. And for this purpose, the Faculty has set up a Wang Tha Phra-Sanskrit Studies Centre bus service for its staff and students. Then, for the one year period in which there was a road closure around Sanam Luang area for the Royal Cremation Ceremony of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the bus service moved to set off from the Office of the President building in Taling Chan campus of Silpakorn University. But usually, we board the bus by the side of the road in front of the Royal Thai Navy Club near Wang Tha Phra campus.

On January 15, 2018, the first day of term and the first day of the service’s return to the Royal Thai Navy Club, I stood waiting for the bus at its usual spot. After a long while, I realized that the Silpakorn University’s bus which was scheduled to leave at 11 am was parked in the farthest reach of the parking lot instead of by the side of the road as was the case before the Royal Cremation. On that bus were three bus drivers: the actual driver of the bus, and two others of the later buses. Sitting at the front, I could listen in on the tortuous conversation between the drivers. They complained of not knowing where to park. Why did the Royal Thai Navy act like they did not know the bus would park there when the Faculty had already contacted them? And when they tried to park in the regular place out front, they feared trouble with the traffic police. Should they contact the Phrarachawang Metro Police Station which is nearby? What should they do with the orange traffic cones blocking the way? What if they get a parking ticket? What would the officer write on the ticket? And much more. Their conversation got me thinking about the idea of ownership, of power over, and the value of a place. Every inch of ground we step on is owned by someone. The overlapping claims of ownership multiply even further when one reaches the inner Bangkok areas like the Rattanakosin island.

Note: The next morning I waited for the bus at its new spot only to find that it had again moved. After leaving the Sanskrit Studies Centre, the university bus stopped in front of the Royal Thai Navy Club and waited for the passengers to board only for a few minutes.

While power, ownership, value and price are fictional constructs when lands are concerned, they are of utmost importance to our worldly life. Of course, the value of each property differs according to the factors that affect its investment value. The gain from a land isn’t only limited to the agricultural produced from its fertile soil. It relates to a range of businesses, especially tourism and real estate, both of which connect intimately with the setting of the property. The closer to the capital city it is, the higher its price.

Not counting the means of inheritance, it is almost impossible to acquire a house in Bangkok today. Even a condominium unit spanning only a few square meters comes with a sky-high price. When a 22-square-meter room in Bangkok costs as much as acres of land in the countryside, one option for the middle class is to buy either new or old houses (sometimes very old) in the suburbs. Still, the suburbs are not all affordable. Suburban Bangkok, particularly Rachapreuk and Salaya areas, are covered with housing developments for the super rich with homes costing tens to a hundred million baht. Land is as valuable as gold.

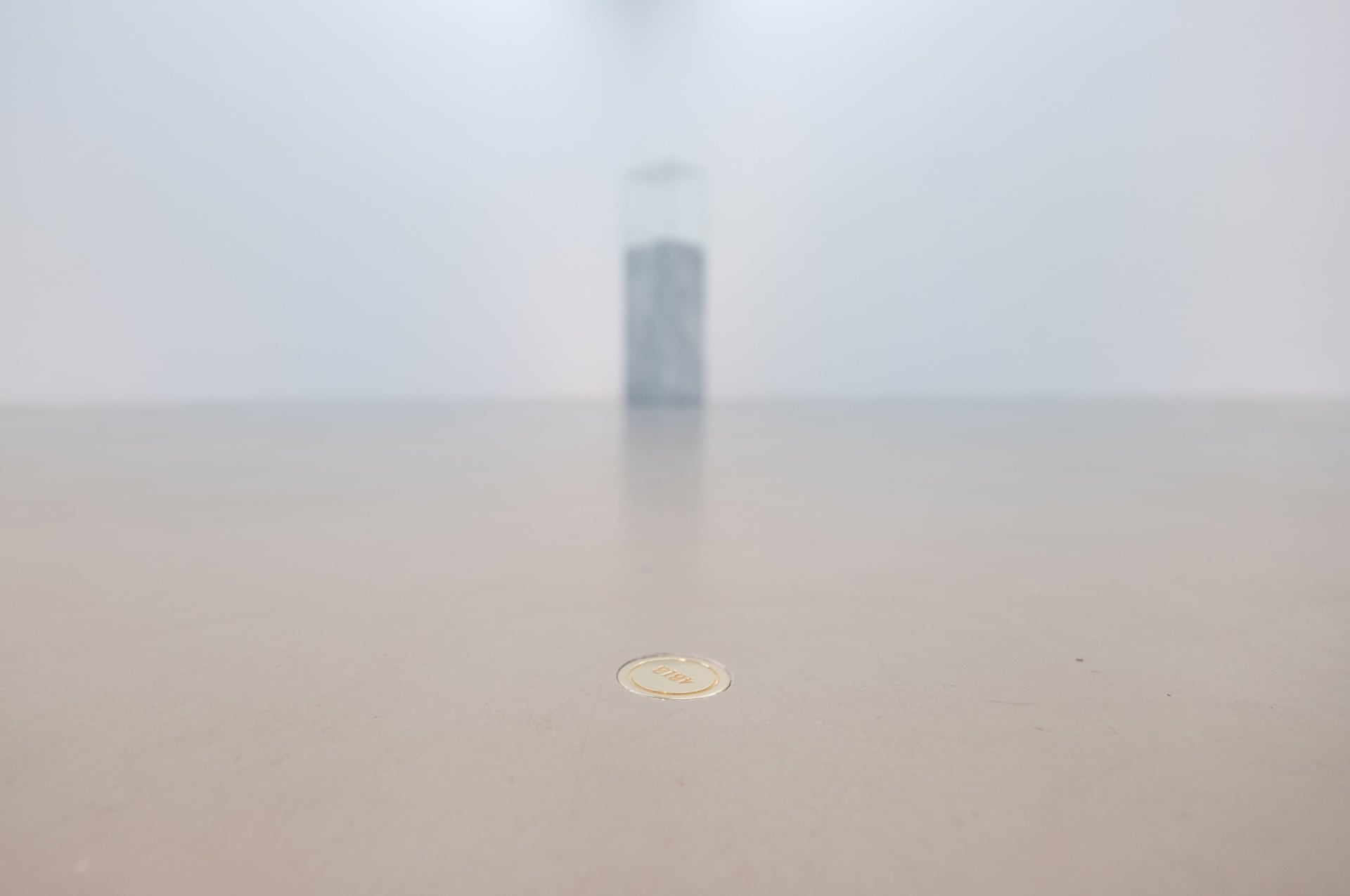

In “The Broken Ladder”, an exhibition by Wantanee Siripattananuntakul, four tiny 18k-gold rivets dot the floor of the exhibition space representing the boundary marks of the artist’s own piece of land. For this artist and college lecturer with no executive position, her 50 square wahs (approx. 200 sq. m.) in the suburb has costed her a fortune. There is a discrepancy between her impression of its price and how the super rich seem to feel about the 35-100 million-baht price tags of their homes. For them, it seems to have felt like nothing. A voice from the video clip being played in the small room relates how one hundred out of 234 detached houses in one ultra-lux housing development have already been sold. Near the end of the clip, a real estate agent (not her actual voice, but the content is real) reassures her potential client: “If you buy this today, we can give you a discount from 41 millions to 33 millions.”

Economic disparity manifests itself through the relationship between the different elements in the exhibition. Conjured by the voiceover in the video clip, a housing development valuing in the hundreds millions takes shape in the mind of the visitors. Not only revealing the prices, the voice also relates information about the location and facilities of these houses, which “are inspired by world-class Mediterranean architecture.” Despite not seeing real footage from the development, through a video clip shot out of a car’s window as it passed through Bangkok’s suburban landscape, one can discern clearly how out of place a house of that style would look in the Southeast Asia region with its hot and humid climate. As if we are not wealthy enough to enter its territory, all we see is the area surrounding the development, which is part derelict land and part terraced or old detached houses.

The modest home of Wantanee also does not make an appearance in the exhibition room. Nevertheless, through the gold rivets driven into the floor based on the calculation of the house’s footprint in relation to the exhibition space, the visitor’s mind imagines her house. This image is buttressed by the title deed which has been blown up to 12.5 times its original B4 size, etched onto a pane of glass so that the visitors can fully take in the house’s plan on the deed. This 6×2.25-meter glass pane reminds one of how big and fragile the dream of owning a house truly is, just one detached house on a land proportional to it—the shared dream of the middle class.

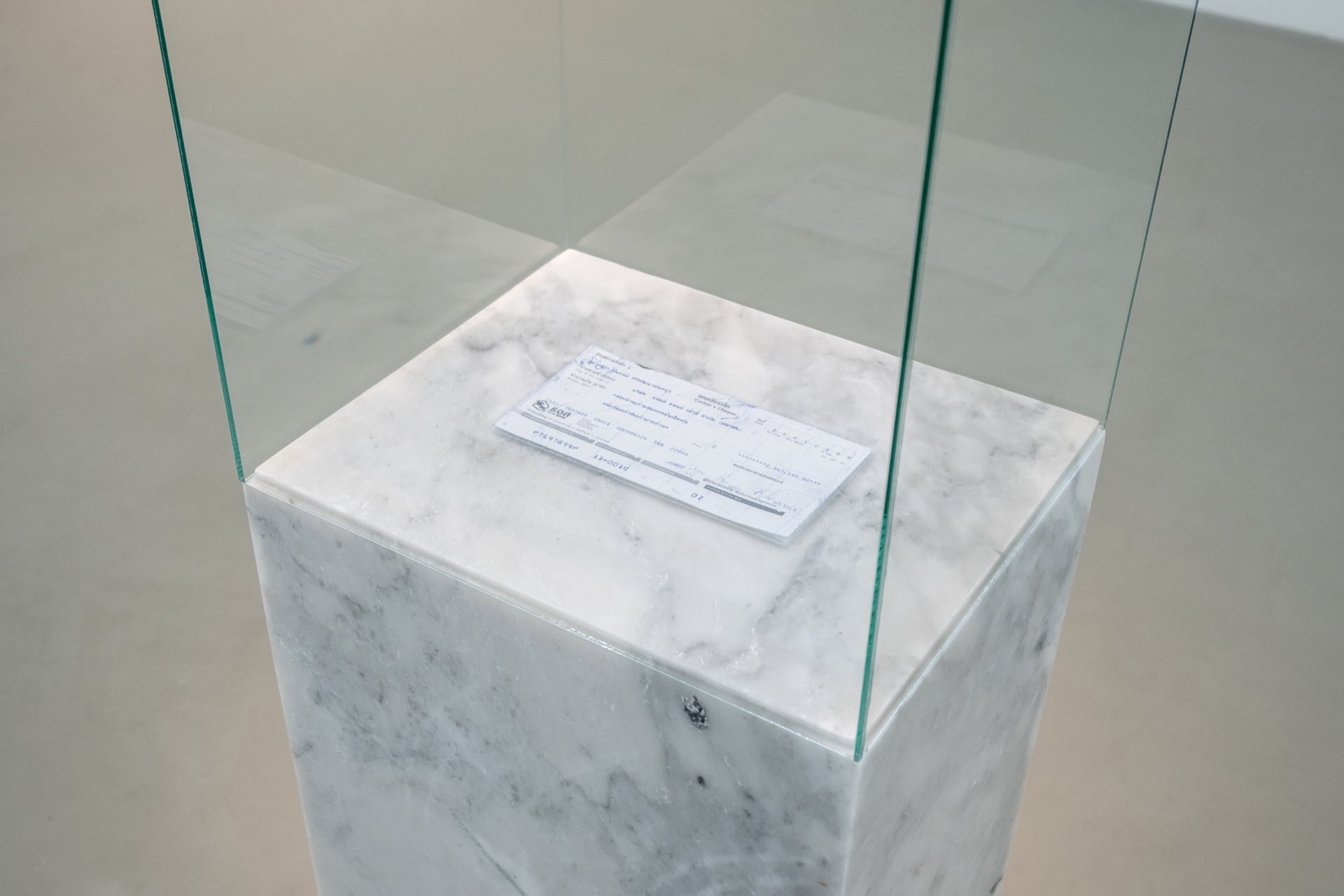

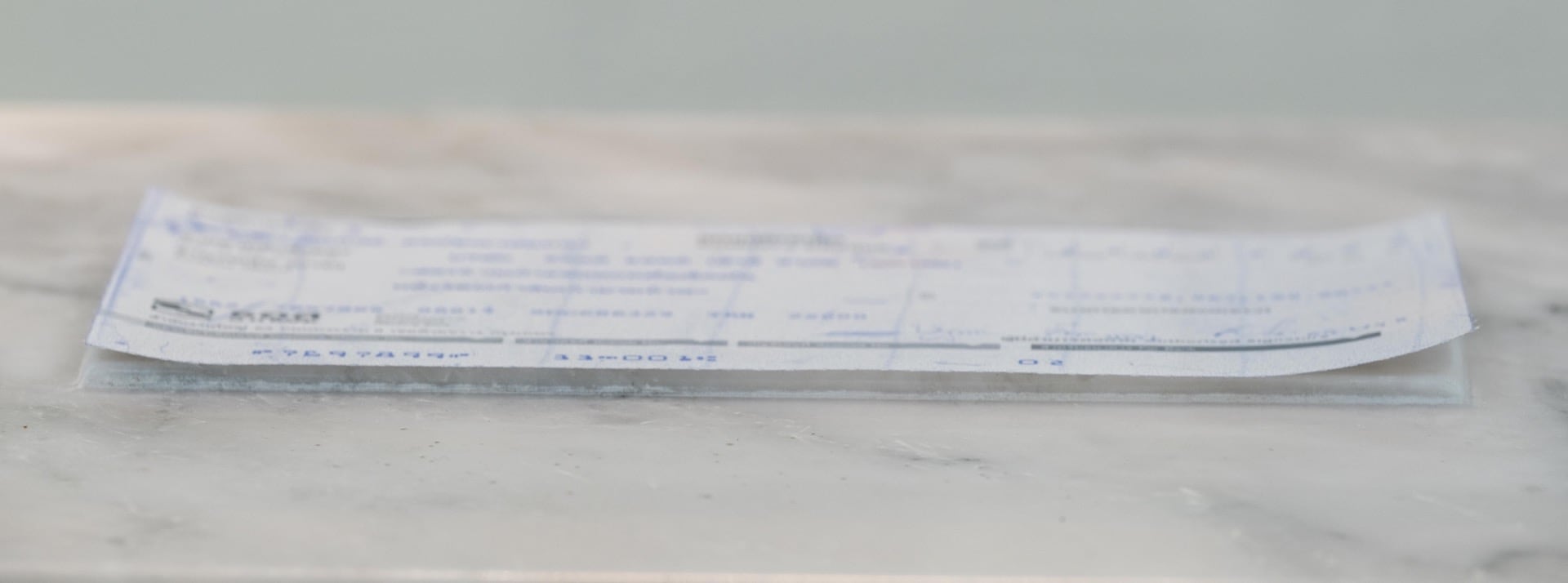

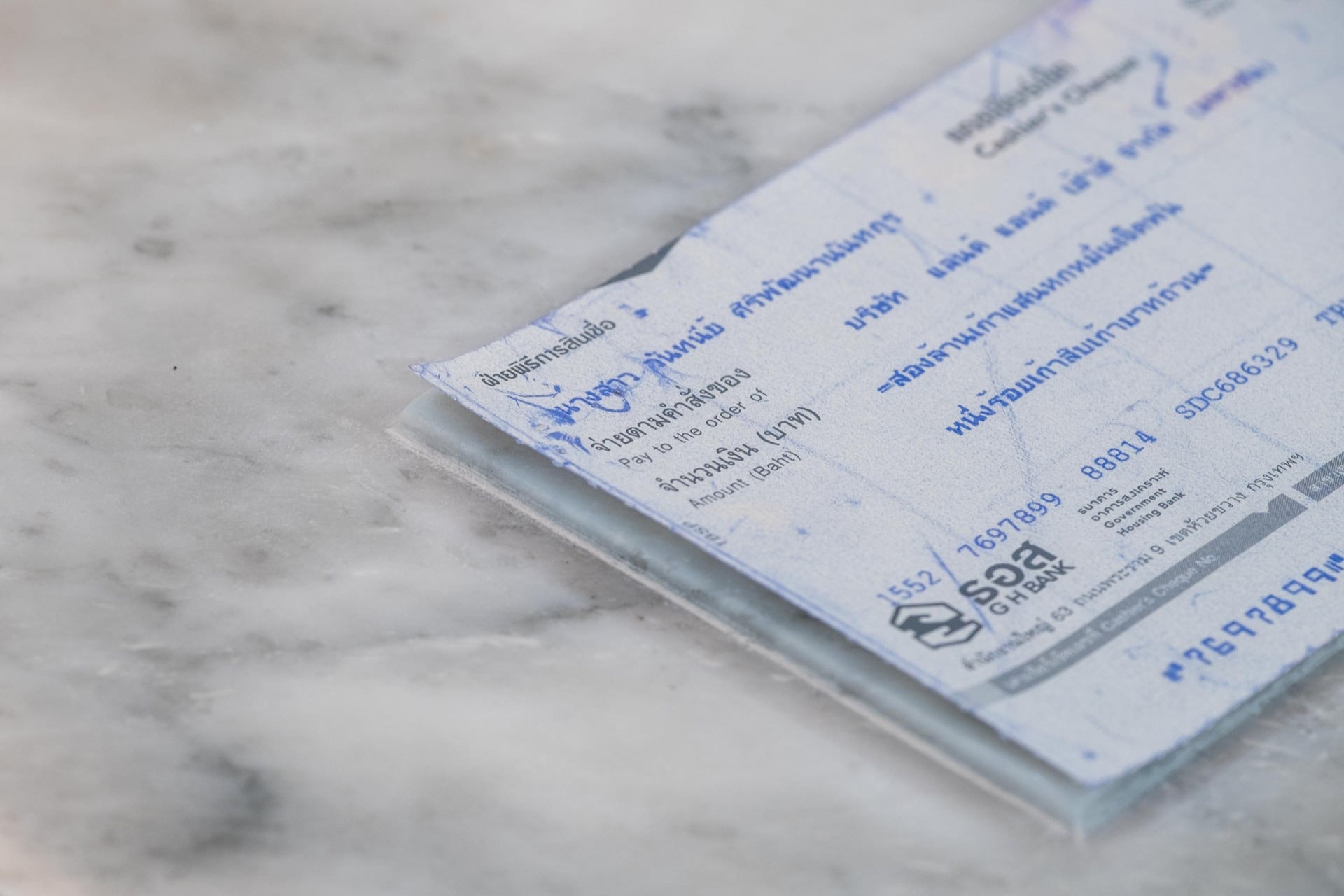

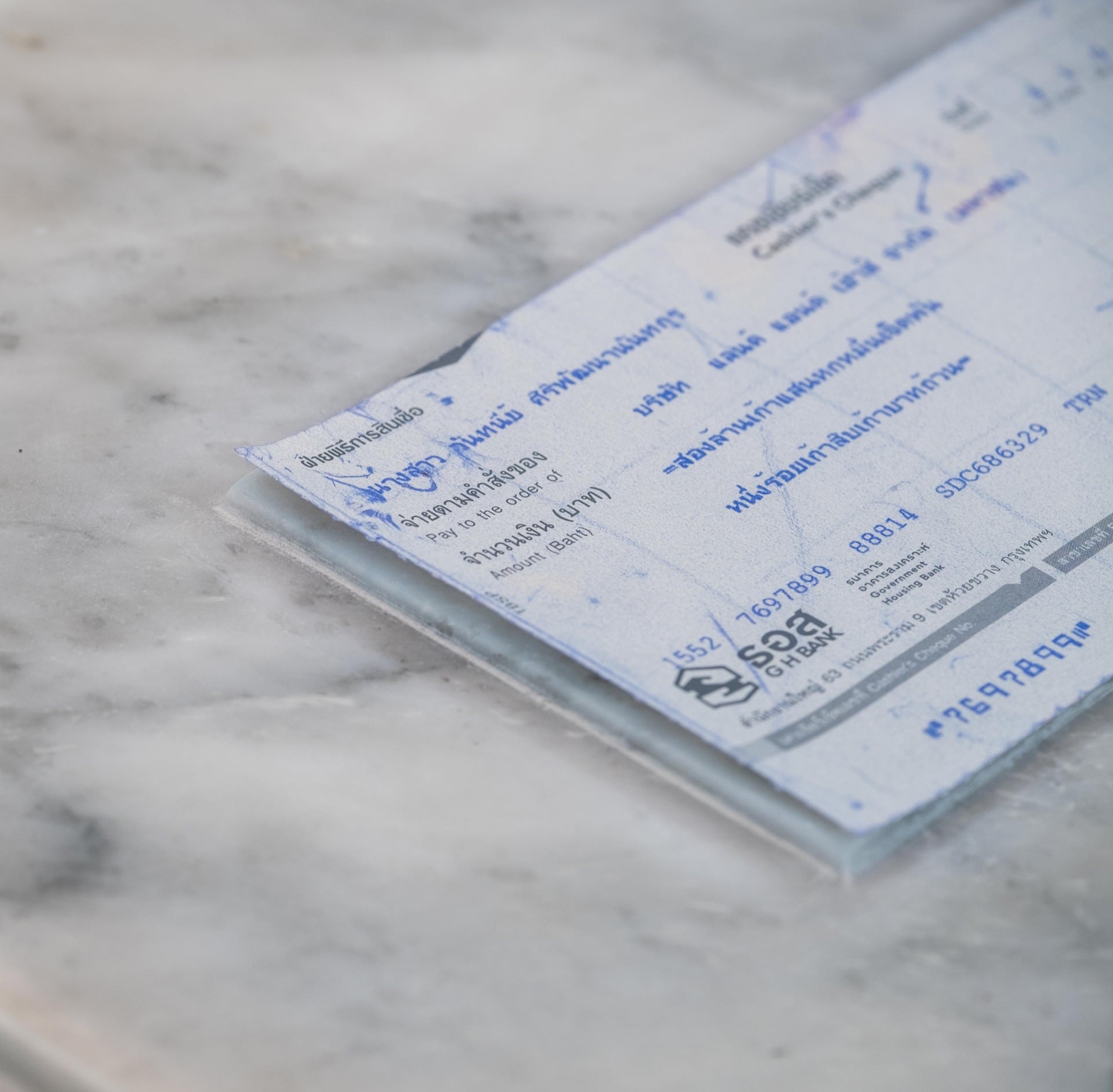

Commanding the space in the middle of the room is a 200-kg marble pedestal. While it looks like a pedestal for some valuable sculpture, inside the acrylic box is actually a photocopy of the cheque that Wantanee used to purchase her house. Is art truly invaluable? When compared to the basic needs like a place of shelter (whose price is far from basic), art worths almost nothing, especially when the artist has to peddle her works to earn enough money for a home. Unless one is a world-class artist, a work of art cannot earn enough even to buy one half of a house. In the case of Wantanee, what enabled her to purchase her home isn’t the art she created. It was in fact her job as an art lecturer at a public university that served as a guarantee that she will be able to pay the mortgage for the decades it would take to do so.

Thus “The Broken Ladder” explores the illusory dream of climbing the social ladder in a modern state where social welfare is pretty much absent. Only the top-tier citizens can afford to prosper. Have you ever heard of the saying “money begets money” or “cheaper by the dozen” or “the richer you are, the better the deal”? When we buy in bulk, the unit price goes down. Yet many people cannot afford to make purchases in this way, since they only have enough to buy one piece of each thing. In these cases, progress on the social ladder is nigh impossible, and being frugal doesn’t seem to offer much relief. A proper home is one of the essential elements of a good life, as the saying goes: “Home is where the heart is.” But to own a home one must also accept a mortgage with the bank. The copy of the cheque on the fancy pedestal is a testament to a life lived under mortgage, for even more costly than a piece of art or the millions baht payment is the cost of our time, the decades of our life.

The bitter taste of Wantanee’s work is felt by many in our society. And for a large number of people, mortgaged homes in the suburbs further entail the burden of a loan on a car, since there is no public transport in such areas. How can anyone get ahead under such circumstance? Still, this artistic statement of being in debt has rendered possible one thing that would otherwise be impossible; that is, it layers, one on top of the other, two properties of different values. In the space of the gallery, which represents the art world of power and ownership, and of economic exchange value, a housing development with homes costing in the hundred millions becomes only one component in a work of an artist striving to pay off her mortgage on a 50-square-wah home. In this space and at this time, it is the artist who holds the power to assign meaning and value. While a broken ladder may not lead us to the home of our dream, in the world of art, dreams and imagination continue to fuel our belief in a better future. So we labour on no matter how thorny the way or various the falls—because when it comes down to it, we want to believe.

Thanavi Chotpradit

Translated by Pojanut Suthipinittharm